Commercial sexual

exploitation of children (CSEC) is a critical human rights and public health

issue that child psychiatrists and other mental health providers can play an

important role in addressing.

Although commercially sexually exploited youth often go unidentified by health providers, these youth may have frequent contact with health care, juvenile delinquency, and foster care systems, and therefore, likely interact with mental health providers who work in these settings.

Although the data on commercially sexually exploited youth are limited, studies show that these youth are at high risk for medical and psychiatric problems and have challenging psychosocial histories, including having experienced childhood abuse, homelessness, and foster care placement.1–4 The exact numbers of commercially sexually exploited youth are unknown given the clandestine nature of the exploitation and underreporting. Experts suggest that the number of sexually exploited children in the United States may be growing.1

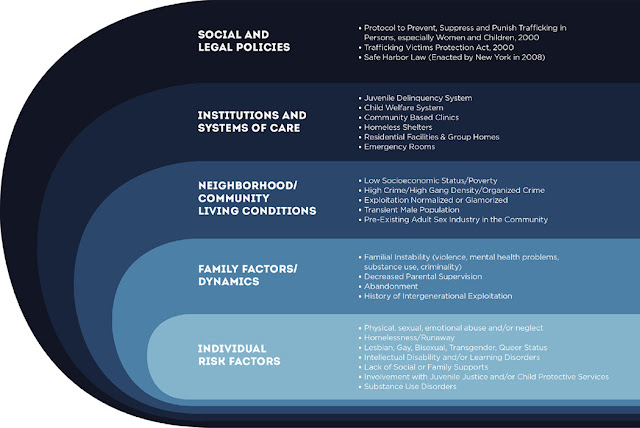

Understanding the risk factors for commercial sexual exploitation, the health and mental health implications, and treatment options can help improve detection and care for this underserved population.

Although commercially sexually exploited youth often go unidentified by health providers, these youth may have frequent contact with health care, juvenile delinquency, and foster care systems, and therefore, likely interact with mental health providers who work in these settings.

Although the data on commercially sexually exploited youth are limited, studies show that these youth are at high risk for medical and psychiatric problems and have challenging psychosocial histories, including having experienced childhood abuse, homelessness, and foster care placement.1–4 The exact numbers of commercially sexually exploited youth are unknown given the clandestine nature of the exploitation and underreporting. Experts suggest that the number of sexually exploited children in the United States may be growing.1

Understanding the risk factors for commercial sexual exploitation, the health and mental health implications, and treatment options can help improve detection and care for this underserved population.

Psychiatric interview: potential associated signs, mental health

symptoms, and red flags for detecting commercially sexually exploited youth

Appearance and behavior

Appearance and behavior

- Youth is accompanied by an individual that appears controlling or does not want the youth to be interviewed alone

- Youth displays a withdrawn, frightened, or guarded affect

- Youth gives vague or changing demographic information

- Youth appears intoxicated or impaired by substance use

- Youth has evidence of branding or tattoos (including facial tattoos, gang-related tattoos)

- Youth has evidence of physical injury (scars, burns, lacerations, fractures, traumatic brain injury)

- Youth appears to be in poor physical health (evidence of skin infections, poor dentition, malnourishment)

- Youth is carrying large amounts of money or expensive items that appear beyond the youth’s means

- Youth has a history of homelessness (includes running away, being abandoned, or forced to leave home)

- Youth has an older boyfriend and/or history of multiple sexual partners

- Youth has a history of juvenile justice system involvement

- Youth has a history of involvement with child welfare services (including living in a group home/foster care home)

- Youth does not attend school or is frequently truant

- Youth has a history of pregnancy, abortion, ectopic pregnancies

- Youth has a history of multiple sexually transmitted diseases, pelvic inflammatory disease

- Youth has frequent emergency room visits (including for physical injuries, reproductive concerns, or sexually transmitted diseases)

- Youth has symptoms of depression

- Youth is suicidal

- Youth has symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder, traumatic stress, and/or anxiety symptoms

- Youth has symptoms of a substance use disorder

- Youth has problems with anger

- Youth has self-harming behaviors

- Having these signs does not mean that a child is being commercially sexually exploited, and lack of these signs does not rule out that a child is being commercially sexually exploited.

Full article at: http://goo.gl/P7PRRH

By:

aVA HSR&D Center for the Study of

Healthcare Innovation, Implementation & Policy, VA Greater Los Angeles

Healthcare System, 11301 Wilshire Boulevard, Building 500, Room 1601, Office of

Healthcare, Transformation and Innovation, Mail Code 10–C, Los Angeles, CA

90073, USA

bDepartment of Medicine, David Geffen

School of Medicine, University of California Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA

90095, USA

cIntegrated Substance Abuse Programs,

Department of Psychiatry and Biobehavioral Sciences, Semel Institute for

Neuroscience and Human Behavior, University of California, Los Angeles, 11075

Santa Monica Boulevard, Suite 100, Los Angeles, CA 90025, USA

dDepartment of Pediatrics, David Geffen

School of Medicine, University of California Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA

90095, USA

eDepartment of Neuroscience and Human

Behavior, University of California Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA 90095, USA

fChild Forensic Services, Department of

Psychiatry and Biobehavioral Sciences, Semel Institute for Neuroscience and

Human Behavior, University of California Los Angeles, 300 Medical Plaza, Room

1243, Los Angeles, CA 90095, USA

*Corresponding author. Email: ude.alcu.tendem@idooshgamidajir

More at: https://twitter.com/hiv insight

No comments:

Post a Comment